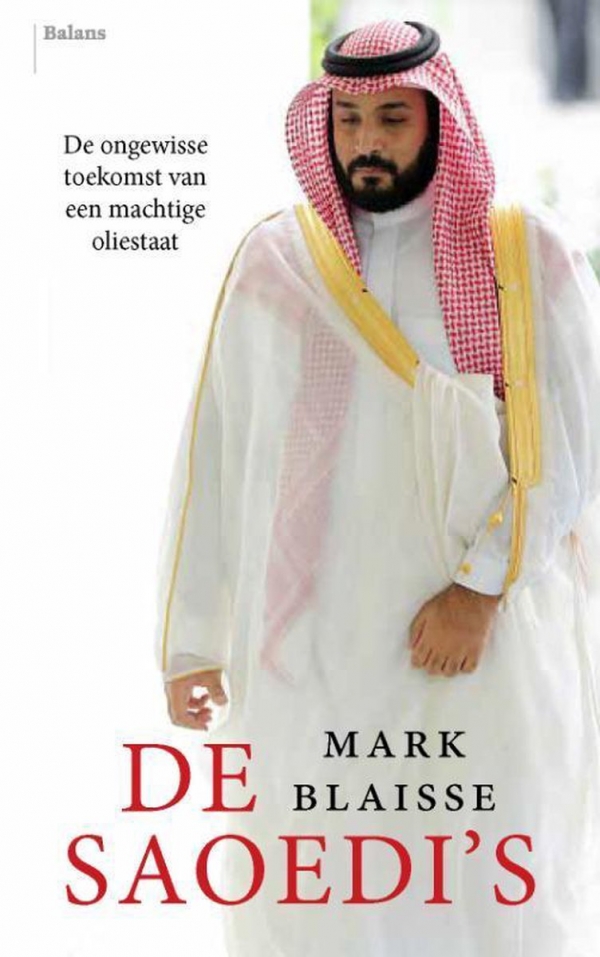

The Saudi’s

The Saudi’s

The Uncertain Future of a Powerful Oil State

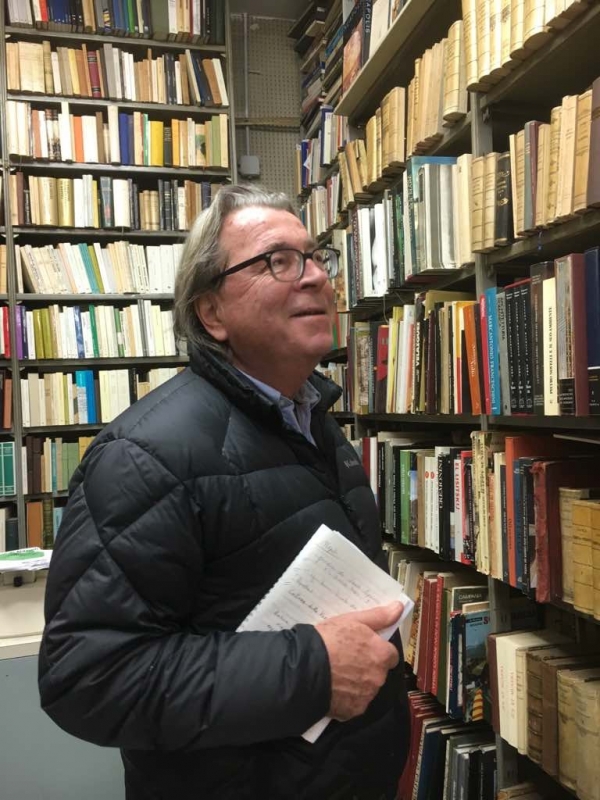

Mark Blaisse is historian, writer and journalist. Since his first book, Anwar Sadat. The last Hundred Days (1981), he has shown a keen interest in the Arab world, its culture, politics, people and religion(s). He has covered the Iran-Irak war for Dutch television, as well as the civil war in Lebanon (Israeli invasion / Sabra-Shatila massacre in 1982) and he spent lots of time researching for his book on terrorism, in Damascus, Beirut and the Beka’a valley.

Mark Blaisse is historian, writer and journalist. Since his first book, Anwar Sadat. The last Hundred Days (1981), he has shown a keen interest in the Arab world, its culture, politics, people and religion(s). He has covered the Iran-Irak war for Dutch television, as well as the civil war in Lebanon (Israeli invasion / Sabra-Shatila massacre in 1982) and he spent lots of time researching for his book on terrorism, in Damascus, Beirut and the Beka’a valley.

In 2019 he published the first comprehensive book in Dutch on Saudi-Arabia, focusing on the period after the arrival of king Salman (2015) and his son Muhammad bin Salman. He spent many weeks in the kingdom to unravel a few of the secrets of this closed society.

One of his latest works is on the Neapolitan philosopher Giambattista Vico.

Mark Blaisse works and lives in Amsterdam. He has two sons and two grandchildren.

Mark Blaisse about The Saudi's (Dutch langage)

Modern Saudi-Arabia is a mystery, only known to most people by key words like filthy rich, Mecca, Islam, oil, desert and, recently, murderous. Ever since crown prince Muhammad bin Salman started his ambitious and controversial modernization program, things started shifting in Saudi Arabia. How will a once secluded desert culture react to the challenges of the twenty-first century?

Historian and journalist Mark Blaisse travelled extensively through the country to find answers to this question. He spent the night with princes in a desert camp, inspected the road to Mecca, picked dates, visited a soccer match and art galleries filled with forbidden work and marveled at the adequate flirting in shopping malls. He discovered a paradoxical and amazingly open Saudi Arabia, a world the average media seem to miss.

In this fascinating account of a country in turmoil he unveils the tensions between traditionally conservative values and an open society with women driving cars, mixed class rooms, theaters and fun parks. Even tourists are welcome again. Or is it a fata morgana after all?

Publisher : Balans, Amsterdam

Chapter 1: The desert camp

Few experiences bring the visitor as close to the Saudi Arabian culture than spending a weekend in the desert. While families in Europe take off to their cabin in the woods or their cottage near the beach, the Saudi men tend to jump in their V8 desert monsters and drive to their isolated tents or farms. The women stay at home, for weekends are a man’s business. His friendships are profound and lengthy and are his most valuable asset. Most men make friends in high school and stay friends for the rest of their lives. They go to university together and, later in life, meet a few times a week to play cards, drink tea, discuss and spend time in camps in the middle of nowhere, away from noise and pollution.

One such group of friends leaves Riyadh every Friday morning and drives for two hundred miles in northerly direction to arrive at a couple of tents on a sandy hill. They park their Ford Raptor and Nissan Patrol Platinum near the informal domain of Faisal, a former army general, whom the others have known since childhood. Faisal sets up camp every November and has it dismantled in March when temperatures start reaching 40 degrees. There is a black, square tent for meetings (majlis) around a central fire place, while three sleeping tents have been positioned next to a restauration tent, a kitchen tent and a water truck. A huge caravan on wheels awaits the guests in case of a sand storm while the dogs have their own tent in the back of the compound. The dogs are used for hunting hare, but the friends prefer to fly to the Sudan or Mali where they can find the real stuff: deer and antelopes. ‘They don’t run faster but they are fitter. Our dogs always win’ says Muhammad, a retired marble stone trader. Like his friends he wears a red and white checkered ghutrah on his head, the traditional scarf, and a long, brown winter coat made of camel hair (bisht or mishlah). While the wives and daughters stay at home, sons are most welcome. ‘We prepare them for a life amongst friends, teach them how to build a fire, why being hospitable is so important, just like path finding and navigating in the desert. We don’t let the boys exchange our traditions for games on their tablets.’

This Friday, five sons join the party. They kiss their fathers on the forehead while the family friends are greeted with three kisses on the cheek. Respect for the elderly is a corner stone of the Arab civilization, just as caring for the sick and poor, feeding strangers and praying five times a day. ‘Here in the desert we only have to pray two or three times. We are, after all, travelling and therefore slightly handicapped.’ Faisal jokes about his own hypocrisy. Only about half of the men retire around noon and then again around half past four into the improvised ‘prayers’ tent. The other half stays put on the thick carpets and plays cards while sucking on a water pipe. Squatted, Hassan makes coffee above the fire. He brought his own, worn, coffee suitcase, filled with roasted beans and the right spoons and tongs. ’The Japanese have their tea ceremony, we are more into coffee’ he says, after which he mumbles something like aligato, thank you in Japanese.

This Friday, five sons join the party. They kiss their fathers on the forehead while the family friends are greeted with three kisses on the cheek. Respect for the elderly is a corner stone of the Arab civilization, just as caring for the sick and poor, feeding strangers and praying five times a day. ‘Here in the desert we only have to pray two or three times. We are, after all, travelling and therefore slightly handicapped.’ Faisal jokes about his own hypocrisy. Only about half of the men retire around noon and then again around half past four into the improvised ‘prayers’ tent. The other half stays put on the thick carpets and plays cards while sucking on a water pipe. Squatted, Hassan makes coffee above the fire. He brought his own, worn, coffee suitcase, filled with roasted beans and the right spoons and tongs. ’The Japanese have their tea ceremony, we are more into coffee’ he says, after which he mumbles something like aligato, thank you in Japanese.

Like his companions, Hassan travels the world regularly for business and pleasure. They all received their degrees from American universities. Saud and Salman wear a baseball cap under their scarf, a proof of the double identity many Saudi’s seem to have. They sometimes find it difficult to choose between modernism and tradition. They love the US, but prefer their own country, despite the limited freedom even the elite experiences. They admire the horizontal American society but hang on to their tribal traditions and social stratification. Changes like the right for women to drive a car, the pushing back of the aggressive religious police, the authorization of a public appearance of a female pop artist (the Lebanese Hiba Tawaji, in December 2017) and the reintroduction of cinema’s after a forty-year ban are looked upon with suspicion by the conservative majority. After all, Islam dictates that nothing must interfere with serving Allah. Austerity and purity are therefore required, which explains the question marks accompanying the energetic change proposals by crown prince Muhammad bin Salman, usually referred to as MBS, during the past few years. ‘He has no choice’ says liberal minded Faisal. ‘He is only thirty-three himself, the neighboring countries are liberal, the seduction reaching everyone via social media cannot be stopped. Saudi Arabia cannot continue putting its head in the sand.’

The word ‘tradition’ is often heard in Saud Arabia. The men in the camp have important jobs, there are emirs among them, cousins of king Salman, diplomats, officers and business men. But during the weekend away they are all equal and the more time passes, the more they behave like Bedouins. ‘Even in Riyadh we stick to our old rituals’ says Faisal, who knows the desert like his pocket. Every year he looks for a new location for his tents, always near sand dunes. He takes his sons for a dazzling ride in his Raptor, sometimes on two wheels, over ridges and through dried beddings, where camels are desperately looking for grass. ‘These days they only serve as status symbols for their owners. Camels destroy our nature because they eat everything that grows. But we cannot forbid them, as they are the symbol of our country ’ laughs Saud.

The word ‘tradition’ is often heard in Saud Arabia. The men in the camp have important jobs, there are emirs among them, cousins of king Salman, diplomats, officers and business men. But during the weekend away they are all equal and the more time passes, the more they behave like Bedouins. ‘Even in Riyadh we stick to our old rituals’ says Faisal, who knows the desert like his pocket. Every year he looks for a new location for his tents, always near sand dunes. He takes his sons for a dazzling ride in his Raptor, sometimes on two wheels, over ridges and through dried beddings, where camels are desperately looking for grass. ‘These days they only serve as status symbols for their owners. Camels destroy our nature because they eat everything that grows. But we cannot forbid them, as they are the symbol of our country ’ laughs Saud.

The Yemenite servants bring mint tea and dates. The men discuss politics and the consequences of the latest changes. What will happen if a woman creates a car accident. That will mean a huge organization considering that women can only be interrogated, searched, arrested and jailed by other women. Female assistants at a gas station? They can hardly imagine such a scene. ‘I don’t see them changing a tire in fifty degrees’ jokes Saud.

The cooks have slaughtered a sheep and prepared a big plate of saffron rice. Seated at a long table we eat stomach, lung, heart and testicles and have homemade cake as a desert. Thereafter we go back to the black tent where it’s warm and cozy, while the outside temperature nears zero. Later we will twist ourselves into military sleeping bags lined with artificial fur, but first we have to talk. In the dusk we look like a secret bunch of tribal leaders who just stepped down from their camels and are preparing a coup, except that all of us are regularly sending or receiving messages on our mobile phones. Outside the tent we drink a mouthful of scotch out of paper cups. The sons are not allowed to see their fathers sipping alcohol, but a Friday without booze is a lost Friday.

Fahd is a former professional soccer player, but he ate so many dates during the past years that he is hardly able to walk. He leans on his cane with its silver knob, caresses his huge belly and starts yelling at the moderns. ‘I will never send my daughter to the US. She would be looked at by men, or, even worse, touched by them. In that case I would have to fly over seas to take revenge and save the family honor. Amongst us there are fathers who allow their daughters to walk unveiled. Believe me, that is the beginning of the end. Women are forbidden to show even the smallest part of their body, they belong to their husbands and to nobody else.’ His friends laugh and tell me that Fahd hasn’t even got children, let alone a daughter, that he is divorced, lives alone, is a flirt and, with that, extremely rich. Like the others he has attended the Royal School for princes. After his graduation he left for Pittsburg where he studied after being offered a royal grant, part of the king’s ambition to propose the best education to as many citizens as possible.

‘When Fahd was still skinny girls were running after him. They like brown eyes and black beards in Pittsburg. After all his conquests it is easy for him to pretend being a prude hero’ says Muhammad. The marble dealer is a born bully and Fahd is his favorite target. But the conservative provocateur has a thick skin. He keeps on protesting against the reintroduction of cinemas. ‘Romance and sex, that’s what it’s all about in movies. Women will only get bad ideas when watching them.’ And men? Asks Muhammad. ‘They are all made up of dirty ideas. But that’s OK’ is Faisal’s predictable answer.

‘When Fahd was still skinny girls were running after him. They like brown eyes and black beards in Pittsburg. After all his conquests it is easy for him to pretend being a prude hero’ says Muhammad. The marble dealer is a born bully and Fahd is his favorite target. But the conservative provocateur has a thick skin. He keeps on protesting against the reintroduction of cinemas. ‘Romance and sex, that’s what it’s all about in movies. Women will only get bad ideas when watching them.’ And men? Asks Muhammad. ‘They are all made up of dirty ideas. But that’s OK’ is Faisal’s predictable answer.

His friends laugh at his wit, while new themes come to the table. Whether they discuss the environment or Donald Trump, the war in Yemen or the price of a gallon of petrol, they almost always fight. But they do agree that the Arabs had an essential role to play in the world’s history: without them knowledge and civilization wouldn’t have spread all over humanity. ‘The Chinese were brilliant but never crossed their boundaries, while we, the Arabs, brought taste, culture, architecture, mathematics and astronomy on camelback to all of you.’ After these words the sociologist Saud is beaming with pride. But the atmosphere becomes grim a soon as Fahd says he is doubting the truth of the Holocaust story. He doesn’t accept the indignation of his friends and repeats that the whole thing is a marketing trick. Saud tells him that he can count on the Germans to have their statistics right and that six million Jews must indeed have been killed. Host Faisal interrupts. ‘It is of no importance how many Jews exactly have died, what matters is that they have been killed. If their neighbors had been more courageous it might not have happened. Let this be a lesson for us, that we will never allow our people to be carried off.’ The men sip their tea and munch on their own thoughts.

All thirteen men present know their European history as well as the Arab one. They show off with the names of treaties and discoverers, citations out of a speech by president Roosevelt for king Ibn Saud, the founder of the Saudi kingdom. They actually fight to be able to impress me. For this group of friends everything seems to be a competition. ‘We picked that up in America’, Faisal admits.

It is almost midnight when the bulky Fahd decides to leave the camp. He walks off a few hundred yards and lays down under the stars. The sound of the generator irritates him. Besides, he likes to sleep naked and that would be impossible even in a tent with only men.

Mark Blaisse

« Elle est ma pensée, Psyché si l’on veut, la Muse comme on disait jadis : moi et un certain idéal que j’ai non seulement de la jeune fille et de ses songeries, mais d’une âme féminine, très douce et pure, très tendre et rêveuse, très sage et en même temps très voluptueuse, très capricieuse, très fantasque. L’âme que j’ai dû avoir dans une autre existence, lorsque l’homme n’existait pas encore et que tout le monde avait encore un peu une âme de jeune Ève. » (extrait d’une lettre de Charles Van Lerberghe à Albert Mockel, décembre 1903)

« Elle est ma pensée, Psyché si l’on veut, la Muse comme on disait jadis : moi et un certain idéal que j’ai non seulement de la jeune fille et de ses songeries, mais d’une âme féminine, très douce et pure, très tendre et rêveuse, très sage et en même temps très voluptueuse, très capricieuse, très fantasque. L’âme que j’ai dû avoir dans une autre existence, lorsque l’homme n’existait pas encore et que tout le monde avait encore un peu une âme de jeune Ève. » (extrait d’une lettre de Charles Van Lerberghe à Albert Mockel, décembre 1903)