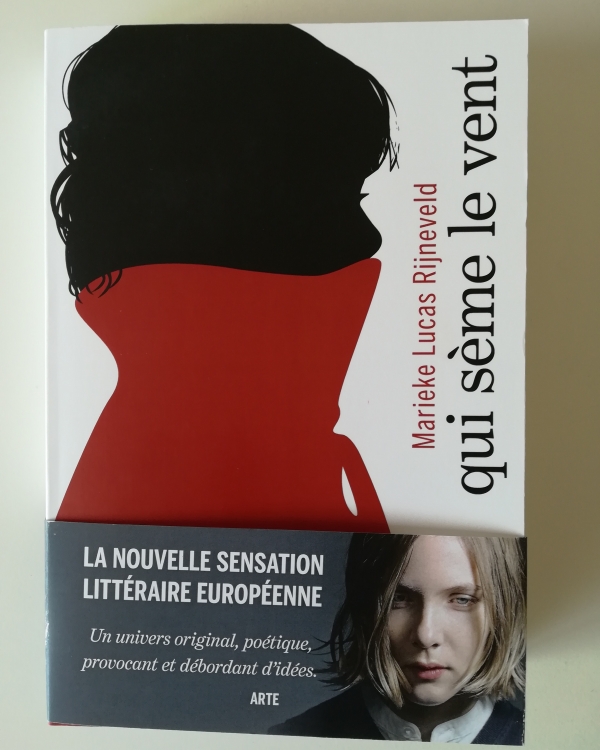

Qui sème le vent, roman de Marieke Lucas Rijneveld

CARTE BLANCHE DONNÉE PAR LE MENSUEL LE MATRICULE DES ANGES À DANIEL CUNIN DANS LA CADRE DE LA RUBRIQUE « SUR QUEL TEXTE TRAVAILLEZ-VOUS ? »

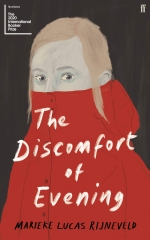

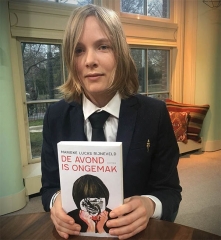

Qui sème le vent a paru en août 2020 aux éditions Buchet/Chastel. Il s’agit de la traduction du premier roman de Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, De avond is ongemak, jeune auteure des Pays-Bas dont on peut lire des poèmes dans notre langue, ainsi de « Caressons-nous les uns les autres » : Poésie néerlandaise contemporaine (Castor Astral, 2019). La transposition anglaise du livre publiée sous le titre The Discomfort of Evening (traduction de Michele Hutchinson) a remporté le 2020 International Booker Prize. Fin 2020, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld a donné un deuxième roman, Mijn lieve gunsteling, dont on peut lire en avant-première un chapitre sur le site des plats-pays.com.

Le champignon de fumée qui s’est élevé, début août, au-dessus du port de Beyrouth nous a rappelé celui d’Hiroshima, soixante-quinze ans plus tôt. Une fois l’origine probable de la catastrophe connue, nos mémoires se sont reportées sur la tragédie de l’usine AZF, survenue à Toulouse le 21 septembre 2001. Parmi les locaux alors touchés par le souffle de la déflagration, on a recensé ceux abritant les Presses universitaires de la Ville rose. Sous les débris et plâtras de leurs bureaux, une petite disquette noire s’est perdue, celle sur laquelle figurait le fichier de la version définitive d’une traduction que j’avais adressée peu avant à cet éditeur. Lequel a finalement imprimé, sans me consulter, sans prévenir l’auteur, une première mouture du texte et des index, le tout sous une couverture aux illustrations hors sujet pour certaines.

Pourquoi évoquer cette péripétie malencontreuse ? Pour la simple raison que l’objet publié ne restitue pas toujours le travail effectué par le traducteur ou ne donne qu’une faible idée des embûches et autres aléas qui se dressent parfois devant lui, abstraction faite des seules difficultés lexicales et syntaxiques liées à l’original. Ainsi, il arrive qu’un éditeur publie un volume sans prendre la peine de nous soumettre le moindre jeu d’épreuves ; de plus en plus de maisons négligent le travail de relecture, certaines ne prenant pas même réellement la peine de reporter les corrections qu’on leur transmet.

À propos du premier roman de la jeune Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, De avond is ongemak (2018), paru en France sous le titre Qui sème le vent, le problème se situait en amont. En raison d’un manque de sérieux de deux ou trois collaborateurs de la maison néerlandaise pourtant d’excellente réputation, j’ai trébuché, en transposant le texte, sur maintes incohérences et inconséquences. Tandis que Michele Hutchinson, ma consœur anglaise, en relevait quelques dizaines, j’en ramassais une pleine brassée. Cela a supposé de notre part de réécrire certains passages, d’opérer moult retouches, de gommer bien des scories. Autrement dit, un tiers de notre énergie et de notre temps fut consacré, non à la traduction proprement dite, mais à un travail qui aurait dû revenir aux correcteurs et relecteurs bataves. Heureusement, Michele et moi avons eu le temps d’échanger au sujet de ces multiples écueils – y compris avec l’autrice et l’éditeur – avant que nos versions ne partent à l’impression. Depuis, l’original a été réimprimé après un sérieux toilettage.

À propos du premier roman de la jeune Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, De avond is ongemak (2018), paru en France sous le titre Qui sème le vent, le problème se situait en amont. En raison d’un manque de sérieux de deux ou trois collaborateurs de la maison néerlandaise pourtant d’excellente réputation, j’ai trébuché, en transposant le texte, sur maintes incohérences et inconséquences. Tandis que Michele Hutchinson, ma consœur anglaise, en relevait quelques dizaines, j’en ramassais une pleine brassée. Cela a supposé de notre part de réécrire certains passages, d’opérer moult retouches, de gommer bien des scories. Autrement dit, un tiers de notre énergie et de notre temps fut consacré, non à la traduction proprement dite, mais à un travail qui aurait dû revenir aux correcteurs et relecteurs bataves. Heureusement, Michele et moi avons eu le temps d’échanger au sujet de ces multiples écueils – y compris avec l’autrice et l’éditeur – avant que nos versions ne partent à l’impression. Depuis, l’original a été réimprimé après un sérieux toilettage.

Malgré ces avatars du métier, Qui sème le vent se révèle être une première œuvre en prose marquante et forte. Plusieurs scènes resteront à jamais gravées dans l’esprit du lecteur, celles où des animaux connaissent un sort peu enviable, celles aussi où mort, sexualité et cruauté se rejoignent. Âmes sensibles, s’abstenir ! D’aucuns ne voient-ils d’ailleurs pas dans ce roman un excellent vomitif ? L’histoire se déroule pour l’essentiel vers l’an 2000, dans une ferme où une famille élève des vaches et produit des fromages. Un malheur la frappe peu avant Noël : l’aîné se noie alors qu’il patine sur un lac. Dès lors, la vie des parents et des trois autres enfants se fige sous la glace du chagrin et de l’incompréhension. Dans une veine d’une sombreur calviniste traversée d’éclairs d’hilarité, les deux années qui suivent le drame nous sont restituées par Parka, l’une des deux sœurs. Au seuil de l’adolescence, cette gamine, engoncée dans son malaise, perturbée par l’incapacité de ses parents à s’extirper de leur deuil et à deviner sa détresse, perçoit le réel de façon assez tronquée. De ce décalage émerge plus d’une situation soit sordide, soit loufoque. Pourquoi le prénom Parka ? Tout simplement parce la jeune narratrice ne quitte plus ce vêtement censé la protéger du monde extérieur et suppléer au défaut d’affection parentale : « Personne ne connaît mon cœur. Il est retranché derrière parka, épiderme et côtes. Dans le ventre de maman, mon cœur a été important pendant neuf mois, mais depuis qu’il en est sorti, plus personne ne se soucie de savoir s’il bat au bon rythme, personne ne prend peur quand il s’arrête quelques secondes ou quand il bat la chamade sous le coup d’une peur ou d’une tension. »

Dans ses grandes poches, Parka accumule maintes babioles quand elle ne cache pas deux crapauds. Lesquels sont, au fond, ses deux interlocuteurs privilégiés, même s’il lui arrive aussi de s’entretenir avec sa petite sœur et leur grand frère sadique. Le roman est peuplé de mille autres animaux : vers de terre, asticots, poux, poussins, hamsters, chats, corneilles, coqs, lapins, taupes, poules, génisses, taureaux… La fréquentation durable ou éphémère de ces créatures se conjugue, chez Parka, avec une attention particulière accordée à certaines parties de leurs corps et, en parallèle, aux fonctions physiologiques du corps humain. Un intérêt qui revêt par moments une forme obsessionnelle, ce qui transparaît dans une tendance à l’automutilation, à la constipation ou encore dans des questionnements sur l’acte reproducteur. Marieke Lucas Rijneveld excelle dans l’art de tisser des associations d’idées, des plus saugrenues aux plus subtiles, de faire s’entrechoquer le beau et le laid, de lier les détails les plus futiles aux pires tourments de l’âme.

Dans ses grandes poches, Parka accumule maintes babioles quand elle ne cache pas deux crapauds. Lesquels sont, au fond, ses deux interlocuteurs privilégiés, même s’il lui arrive aussi de s’entretenir avec sa petite sœur et leur grand frère sadique. Le roman est peuplé de mille autres animaux : vers de terre, asticots, poux, poussins, hamsters, chats, corneilles, coqs, lapins, taupes, poules, génisses, taureaux… La fréquentation durable ou éphémère de ces créatures se conjugue, chez Parka, avec une attention particulière accordée à certaines parties de leurs corps et, en parallèle, aux fonctions physiologiques du corps humain. Un intérêt qui revêt par moments une forme obsessionnelle, ce qui transparaît dans une tendance à l’automutilation, à la constipation ou encore dans des questionnements sur l’acte reproducteur. Marieke Lucas Rijneveld excelle dans l’art de tisser des associations d’idées, des plus saugrenues aux plus subtiles, de faire s’entrechoquer le beau et le laid, de lier les détails les plus futiles aux pires tourments de l’âme.

Bien qu’elle ait signé deux recueils de poèmes, elle a décliné l’an passé l’invitation du Marché de la Poésie à Paris, préférant se consacrer à son deuxième roman. Pour la rédaction duquel son éditeur saura, sans doute aucun, un peu mieux l’accompagner. Malgré le succès remporté par le premier – traduit en une vingtaine de langues –, la jeune femme continue de travailler quelques jours par semaine dans une ferme, parmi les vaches.

texte paru dans le n° 216 du Matricule des anges, septembre 2020, p. 11,

écrit avant que le roman ne remporte le International Booker Prize 2020.